The Truth About Chemo- and Radiotherapy

“Cancer is the pitbull of diseases, and it had her in its jaws, biting and rending. It would not stop until it had torn her to pieces.” – from Revival, by Stephen King

I have nothing against conventional medicine. Therefore, I am not trying to condemn chemotherapy, nor am I attempting to claim it is terrible and should never be used or has never been successful. What I am saying is that I think the U.S. should provide more funding to oncologists so that they can successfully concoct, at the least, a more direct treatment that targets tumors only and does less damage to healthy cells than chemotherapy and radiotherapy do.

For over 40 years, a disease that author Stephen King referred to as the “pitbull of diseases” has continuously claimed the lives of over eight million people a year worldwide. Survival rates, which can be as low as four percent, have been roughly the same for 25 years. This persistent illness is known as cancer, and occurs when cells grow uncontrollably to form a malignant tumor.

The most common types include breast, lung, prostate, and skin cancer. Nearly half of cancer patients are diagnosed too late, making their chances of survival as low as one percent. Some cancers can be removed surgically, depending on the type and location, while others have to be fought off with the help of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. But are they really helpful?

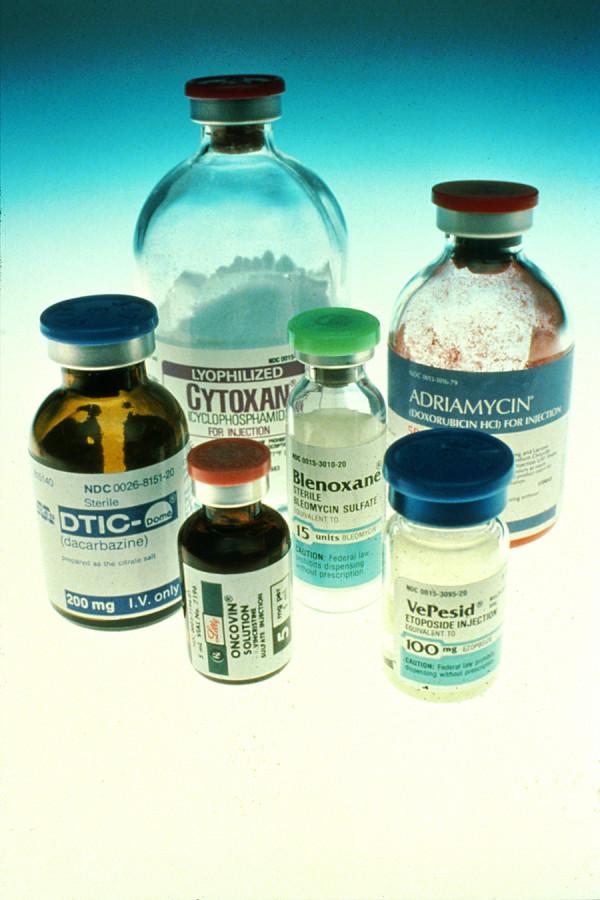

Reports of chemotherapy’s effectiveness are shamefully exaggerated. It works for some cancers, but not all. According to a 14 year study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in December of 2004, chemotherapy is only 2.1 percent effective towards five-year survival for some of the deadliest cancers. Even then, patients were not cancer free after five years, just alive. One reason for this could be that chemotherapy can release a protein that stimulates cancer cell growth, and therefore causes the body to build up resistance. This creates a huge issue, since the only way to give a patient chemo is to give it to them in moderation, giving healthy cells time to recover, so increasing the dosage would eventually produce fatal results.

Chemo is harmful because it is literally toxic poison. In my opinion, it doesn’t make sense to basically poison your body back to health. Chemo attacks healthy cells as well as cancer cells, and therefore carries a number of fatal risks as well as severe side effects that can sometimes cause permanent damage to the body. Patients do not just lose their hair and experience fatigue; they also might experience things like blood clotting and heart arrhythmias. Both of these complications are not always easily treated and therefore could prove fatal. That’s why chemotherapy is usually only used as a last resort, and that’s why a lot of cancer patients don’t even think it’s worth going through it.

“Even if it’s helpful to some patients, it’s harmful to others,” freshman Lin Li Oechsle said. “I think there should definitely be more research or funding going towards alternate ways to fight cancer.”

Radiation carries most of the same side effects as chemotherapy. I’m no radiologist, but I feel uncomfortable with this treatment option as well because if radiation exposure is a common cause of cancer, it does not seem like a great treatment option. Although small, the risk of developing a second malignancy as a result of radiotherapy (or chemotherapy) is in fact present. The most common secondary cancer is bone cancer, which is very easily spreadable to other parts of the body and therefore difficult to get rid of.

However, I am not trying to suggest that chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be immediately stopped because they are vehement killers. It’s a well-known fact that there have been many cases in which both treatments have been fairly successful in common cancers. But it has been almost 70 years since chemotherapy was first used in cancer treatment, and I think it’s time to start focusing on direct treatments that actually make some sense.

Chemo and radiation are both used with the intent to shrink tumors and kill cancer cells, but wouldn’t it make more sense to go to the root of the issue and try to concoct alternative treatments that repair uncontrolled cell dividing and safely demolish tumors without harming healthy cells? I’m fully aware it’s not that simple, but I think by putting more funding towards cancer research, oncologists will have more access to the resources they need to discover valuable information about cancer and come out with safer and more direct conventional methods to tame this pitbull.

“Chemo and radiation are only temporary treatments; they only buy people a couple more years,” junior Brandon Backa said. “It’s probably a better idea to come up with safer treatments.”

After all, what’s more important to oncologists and politicians — saving money, or saving lives?

Senior Sarah Trebicka is a four-year staff reporter and former two-year Our World editor, now serving as editor-in-chief for the Spotlight. In addition...