Colleges Grossly Undermine Campus Assault

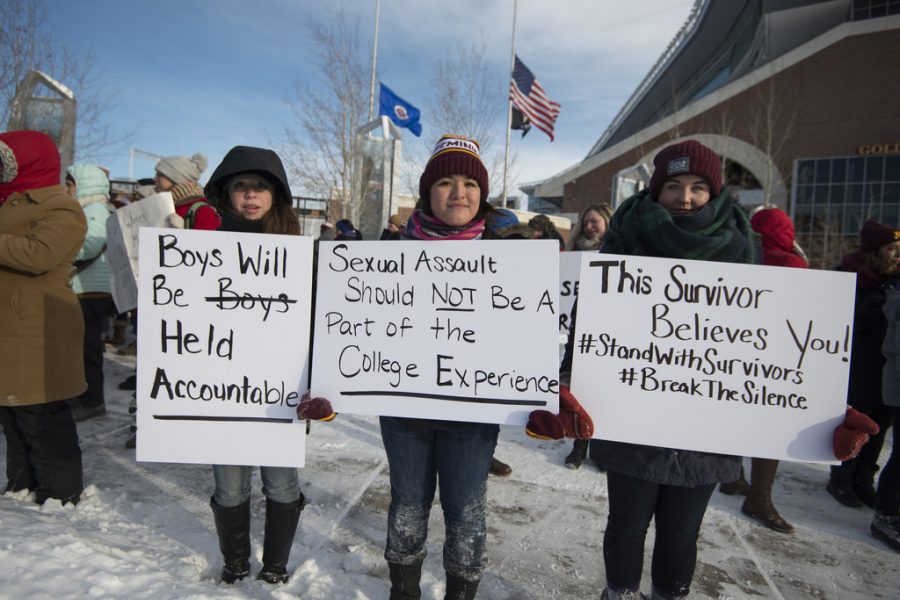

According to a 2016 study by the National Institute of Justice, one out of every four female undergraduates will fall victim to some type of sexual assault before graduation, yet colleges frequently fail to warn students about this risk.

“It makes me sick honestly,” senior Melissa Stough said, “the fact that before we even have to enter the ‘real world,’ women have to face problems like this.”

Despite the pervasive nature of this chilling fact, in 2015, 89 percent of colleges disclosed zero reported incidences of rape to the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act annual data collection, according to a 2017 analysis by the Association of American Universities. This is a cause for concern, as, according to the same analysis, the disclosures plainly fail to line up with research, campus climate surveys, and widespread experiences reported by students: all of which indicate higher documentations of sexual violence than the schools chose to report.

In other words, colleges and universities are epically failing to tell the full story of sexual violence on campuses. What this leads many people to believe is that these schools are deliberately misconstruing and avoiding their Clery obligations to protect their reputations as safe campuses.

For years, colleges have been misclassifying sexual assaults and sweeping them under the rug to avoid reporting them. For instance, many schools wrongly categorize reports of acquaintance rape or fondling as “non-forcible” sexual offenses, which is a definition that legally applies only to statutory rape or incest. In 2008, Eastern Michigan University was fined $350,000 by the Department of Education for a plethora of violations, including miscoding rapes. In fact, the problem has grown so prevalent that the Department of Education now calls schools whenever they submit even one report of a non-forcible sexual offense.

However, the problem extends even further: according to a 2014 U.S. Justice Department survey, only 20 percent of rapes and sexual assaults against college women are actually reported to law enforcement. Therefore, a new question arises: why don’t victims go to the police?

The answer comes right back to the harsh reality of schools mishandling these issues in a self-serving quest to quash any whispers of a sexual assault scandal. Colleges fail not only to properly discipline perpetrators, but to even investigate claims in the first place, thus discouraging victims to report assaults.

“I think that because sexual assault often occurs at parties and other social settings, it’s wrongly taken as normalized social behavior by colleges, which is unacceptable,” senior Sean Duane said.

On Dec. 7, 2012, Florida State University freshman Erica Kinsman reported to law enforcement that she had been raped by a stranger several hours earlier off campus.

According to a thorough examination by the New York Times of the errors in inquiry on Kinsman’s allegations, “there was virtually no investigation at all, either by the police or the university.”

Kinsman eventually identified the perpetrator as Jameis Winston, Florida State’s prized quarterback and a marquee name in college football. The police failed to interview him for two weeks, and obtained his DNA 342 days after the assault, despite the fact that a witness videotaped part of the sexual encounter, Kinsman developed bruises that indicated recent trauma, and tests found semen on her underwear. In fact, by the time the local prosecutor got the case, much of this important evidence had disappeared, and he therefore eventually decided not to prosecute Winston due to insufficient evidence.

Rising from his allegations virtually unscathed, the assailant went on to win the Heisman Trophy, lead Florida State to the national championship, and be selected as the Tampa Bay Buccaneers No. 1 pick in the 2015 NFL draft.

“As someone who will be attending college next year, it’s really disheartening to hear that most sexual assault cases in college go unreported or unpunished,” senior Sydney Dunbar said. “Sexual assault should never be ignored and it should never go unpunished, because someone had the audacity to hurt someone else and take advantage of them, and they should absolutely be disciplined for that.”

Unfortunately, Kinsman’s case is just one of many examples of colleges and law enforcement ineffectively addressing incidents of sexual violence. In 2014, the Huffington Post reached out to 50 colleges and universities for data on how campus sexual assaults are disciplined, and based on data provided by 32 schools, found that less than one-third of students found responsible for sexual assault are expelled.

Action must be taken to address this issue. When campus environments are hostile because of sexual violence, students cannot comfortably learn, and their right to an education free of sexual discrimination as guaranteed by Title IX regulations is at considerable risk.

Schools need to take an honest look at their policies and verify that they facilitate welcome reporting, as well as resources and training to support victims of sexual violence, and to make changes accordingly. They must develop procedures to guarantee proper handling of sexual violence, and to include students, faculty, staff, and community partners in these efforts.

Victimization surveys, for example, can be crucial in documenting both reported and unreported incidents of sexual violence, understanding why survivors refuse to report, and assessing administrative and cultural mishaps on campus that may undermine reporting.

“The majority of guys who commit these sex crimes believe that the girls are asking for it, and that that’s what gives them the right to violate someone,” Dunbar said. “It’s creating a victim-blaming culture in which survivors are looked down upon. People say, ‘Oh, it’s because they dressed a certain way,’ ‘It’s because they were drinking,’ ‘They were too flirtatious,’ and it’s really hard to be a girl in this society where people say those things.”

However, most importantly, we as a society must take a long, hard look at our everyday practices and ask ourselves if we’re doing enough to prevent sexual assault and support survivors, or if we’re failing to foster an environment where survivors feel comfortable coming forward and speaking out.

Senior Sarah Trebicka is a four-year staff reporter and former two-year Our World editor, now serving as editor-in-chief for the Spotlight. In addition...