We will not be your Yellow Peril: the crisis facing Asian American women

Asian American women face unique challenges posed by racial and gender discrimination which have been exacerbated by historical and contemporary media representation.

This third part of the series, We Will not be Your Yellow Peril, covers the unique threats facing Asian American women, and the role that media, specifically entertainment media, has played in creating the circumstances necessary for these threats to develop.

Sex, like race, is a matter rife with issue and concern. The goal of racial equity often exists in tandem with the desire to achieve higher levels of equity between the sexes. Minorities and women have historically suffered from varying levels of marginalization, with discrimination against minority women often worse than what is faced by their male counterparts.

Amidst the current uptick in violence targeting the Asian American community, a separate and perhaps worse situation has emerged: the heightened risks and issues now facing Asian American women.

Women have made up the plurality of victims of hate crimes targeting Asian Americans in the last year, comprising 60% of cases reported by activist group Stop AAPI Hate.

Statistics like these demonstrate the heightened threat posed to Asian American women in particular, while cases such as the rape and murder of Ee Lee, or the stabbing of two elderly women at a San Francisco bus stop only serve to highlight the level of cruelty which these attacks bring.

“I try my best to protect myself, but [it feels like] nowhere is safe for Asian women. In addition to sexism, Asian women [have to handle] racism,” said senior Daisy Jung, who is originally from South Korea. “Whether we stay home or on the street, we are [at risk of being] raped, abused, [or] killed by somebody because of not only our skin color, but also our [gender].”

Tragedies such as the mass shooting at three Atlanta massage parlors which left eight people dead, six of whom were Asian women, have also further highlighted the heightened threats facing Asian American women.

“I don’t think 6 out of the 8 people would be Asian women if race and gender weren’t a motive,” said senior Michelle Li, who is of Chinese descent. “I think it’s pretty obvious, and for it not to be labeled as a targeted hate crime is just being blind to what happened.”

The disproportionate victimhood of Asian American women in the current crisis speaks to a distinct battle within the broader Asian American struggle to fight not only racism, but sexism as well.

Gender and race have played a fundamental role in defining the struggles for equality by marginalized groups. For minority women, the challenges posed by racial discrimination compounded with gender discrimination serve to create unique and perhaps worse circumstances.

The depiction of all minority groups within American media has been a topic fraught with controversies as historical portrayals of marginalized groups from the 19th century to now have often been built upon stereotypes and racist attitudes; the depiction of Asian descendant individuals is no different. Whether it is the embodiment of the “yellow peril” in the form of the villain Fu Manchu, or the portrait of the nerdy Asian archetype, Asians have not been immune to ignorant and racist portrayals within the media, particularly in film and entertainment.

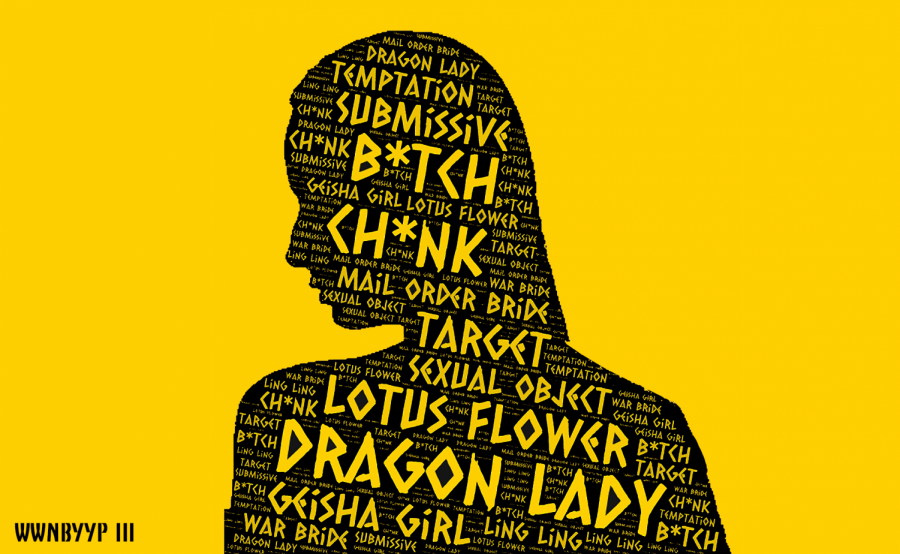

For Asian American women, much of the current racial and gender based discrimination dehumanizes and reduces them to sexual objects, coupled with other stereotypes thrust upon Asians in general. Responsibility for the spread of these stereotypes and perceptions can be most strongly placed upon their perpetuation in media.

The depictions of Asian women in the media take on a noticeably hypersexualized and objectified tone. Common traits attributed to female Asian characters in America’s history have included status as exotic, submissive, overtly sexual in nature, and opportunistic seducers.

“A lot of the time, Asian women, especially in the U.S., are treated as conquests because people view them as exotic or ‘others,’” said senior Helena Munoz, who is of Taiwanese and Columbian descent. “It’s just unfair that people view us that way, and I think a lot of it has to do with media representation. A lot of the time movies, tv shows, and comedians will oversexualize Asian women, and I think…it just degrades Asian women.”

Media presentation of these stereotypes throughout the 20th century and even into the 21st century — in works such as the sexualized Vietnamese female characters of the musical Miss Saigon or the conniving, hypersexualized character of Ling Woo in Ally McBeal — have allowed these perceptions of Asian women to continue, permitting their negative impacts in society to continue as well.

By treating Asian women as submissive, sexual beings, their humanity is erased, and they are seen as objects of lust. The real world implications of these perceptions can be most profoundly seen in the primary targeting of Asian women, and in cases such as the previously mentioned Atlanta shooting.

“What we see in the media can directly translate to [how] people treat [women in real life] who look like what they see on the screens,” Li said. “Obviously, the [Atlanta] shooting was an example of that and although I’d like to believe it has gotten better over the years, recent events have made me question my thinking.”

The perpetrator responsible for the Atlanta shooting described his motives as ones of sexual frustration, viewing the establishments he targeted as the embodiment of the sexual temptations afflicting him. The connection between these primarily Asian establishments being viewed as points of sexual temptation, and Asian women being historically depicted as attractive sexual objects, cannot be overlooked.

The description utilized by law enforcement officials, such as Sheriff Jay Baker, of the shooter’s victims being a “temptation for him that he wanted to eliminate” even more clearly highlights the perpetuation of these ideas even by figures of authority.

“It makes me really upset to see that a leader in the community could brush off a hate crime, a mass murder, as just someone having a ‘bad day,’” Li said. “People have bad days all the time: they don’t kill people, they don’t kill multiple people, and they don’t kill with racist and sexist intent. It makes it seem like it’s ok, and that it’s ok for you to go out and kill eight people. It just downplays the extent and severity of the incident to the whole public.”

Looking beyond the specific horrors of the Atlanta shooting, the particular targeting of Asian American women speaks to a different effect of stereotypes. The depictions of these women as submissive and fragile may embolden the perpetrators of attacks to target a minority group which has been continuously portrayed as unable or too afraid to fight back.

“It’s really sad to see that, because it proves to me that there’s such [a] level of normalization of racism and misogyny, and I think it stems from stereotyping and people feeling comfortable [using] these stereotypes in their everyday life,” Munoz said. “I feel that it has a bigger impact on [Asian American] women because people just think…if it’s ok to stereotype these people, then it’s okay to disrespect them, which leads to violence inevitably.”

The current crisis which faces Asian American women is not one which has emerged abruptly. It is a situation in which the circumstances have been more than a century in the making. If attitudes are to shift, and this current crisis to become merely one dark period instead of the precursor to another, the way Asian women are portrayed and perceived must change. They can and should be represented as who they are: human beings.

“Stop looking at us like [we’re] exotic creatures [that are] so out of this world,” Li said. “We are Americans; we are just human beings. Our race is not an excuse for you to objectify us.”

Senior Lucas Zhang is a second-year staff reporter and Our World editor for the Spotlight. He is also President of Student Council, a member of the Speech...