Should the U.S. Naturalization Test Be a Graduation Requirement?

Name two of the longest rivers in the United States.

Done yet?

If you can’t seem to answer this question, or if your first thought was, “Who cares?” consider this: some immigrants are required to answer this question correctly in order to become naturalized American citizens.

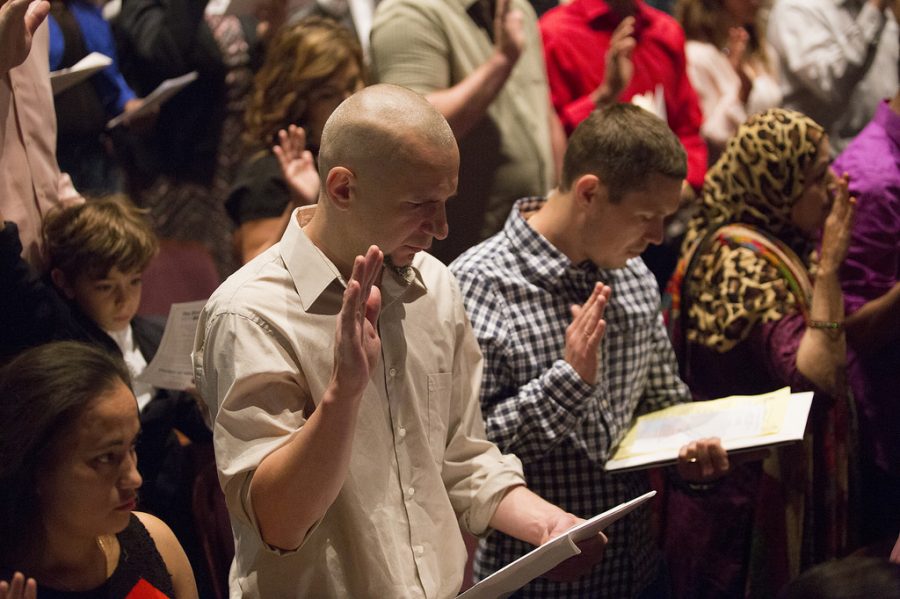

In 2015, over 1.05 million people received lawful permanent residence in the United States, and 730,259 people became naturalized citizens, according to the Department of Homeland Security. In total, there are 42 million foreign-born residents in the U.S., including naturalized citizens, legal noncitizens, and unauthorized immigrants.

In order to apply for naturalization, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) says an immigrant must meet several basic requirements (along with multiple other more individually specific requirements): be at least 18 years of age, be a lawful permanent resident, have resided in the U.S. as a lawful permanent resident for at least five years, have been physically present in the U.S. for at least 30 months, be a person of good moral character, be able to speak, read, write, and understand the English language, and be willing and able to take the Oath of Allegiance. They must also have a knowledge of U.S. government and history, which is where the naturalization test comes in. During the interview process, immigrants are asked up to 10 questions pertaining to U.S. civics, government, history, and geography, and must be able to answer at least six questions correctly, such as “Name a state that borders Canada,” or “During the Cold War, what was the main concern of the U.S.?”

According to USCIS, 91 percent of immigrants applying for citizenship do pass the test, while the Annenberg Public Policy Center found in a September 2014 poll that roughly 35 percent of native-born American adults fail. In fact, another poll by the same organization in the same year found that 79 percent of native-born American adults failed to answer the question, “Who was the president of the United States during World War I?” (Woodrow Wilson). Furthermore, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) found that only 25 percent of high school seniors in 2014 received a passing score on the federal government’s civics exam.

Because of these statistics, some people argue that Americans lack the capacity to exercise self-government because many fail to understand or recognize the fundamental principles underlying American civics and government. They assert that the more educated Americans are, the more likely they are to be civically engaged.

“If the goal of making immigrants pass the naturalization test is to ensure they know enough about the country they’re living in, I feel as though citizens should also have to take the test,” English immigrant and junior Nate Morris said. “Just because citizens are born in the U.S. and grow up there doesn’t mean they know anything about its history. If you want to make sure everyone living in your country knows and respects its history and values, nobody should be exempt from a knowledge test such as that one.”

The Civics Education Initiative (civicseducationinitiative.org), a coalition created in 2013 by grassroots activists working with state and local leaders, proposes that individual states pass legislation requiring students to pass the naturalization test in order to graduate from high school. A similar nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, the Joe Foss Institute, aimed to make the U.S. citizenship test a graduation requirement in all 50 states by 2017.

“Civics is being boxed out of the classroom today by an all-consuming focus on science, technology, English, and math (STEM). Teachers and administrators are being incented to teach content that will be tested – tests that are being used in many cases to determine funding and a host of outcomes for schools, students and teachers,” the Civics Education Initiative website said. “While no one argued STEM isn’t important, the downside is that civics and lessons on the Bill of Rights, Constitution, and how our government works are being left by the wayside. Students are not learning how to run our country, how government is meant to operate as outlined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and more importantly, the history behind how our country came to be: the philosophy behind America’s values.”

Arizona was the first to pass such a law. Starting with the class of 2017, all students are required to pass a civics test based on the 100 questions from the Naturalization Test Study Guide, and they are allowed limitless attempts as long as they pass by graduation.

Fourteen other states, including Wisconsin, Kansas, and Idaho, passed similar laws, some requiring that students score at least a 60 out of 100: the same passing percentage required for immigrants pursuing citizenship.

“I think [high school social studies] covers [the topics on the naturalization test]. They seem basic enough,” social studies teacher and gifted coordinator Mrs. Katie Quartuch said. “I hope that some of that is knowledge students have before high school so that we can do more analytical work. For example, yes, you should know that you have freedom of speech in the U.S., but in high school we look at how we define ‘freedom’ and ‘speech,’ and we question the boundaries in which that freedom exists.”

However, critics insist that such a law would be a meaningful yet empty effort. Joseph Kahne, a professor at Mills College who oversees the Civic Engagement Research Group, argued in a 2015 commentary for Education Week that a testing approach to civic education is equivalent to “teaching democracy like a gameshow.” Others scrutinize the laws by arguing that it places more unnecessary stress and standardized testing on already-overwhelmed high school students.

“I don’t think American citizens should be required to pass this test to graduate high school because they have already proven their citizenship and have experienced the American life already. Requiring students to pass a naturalization test would have very little impact in the real world of the education system,” Pakistani immigrant and junior Rabia Khan said. “Also, the likelihood of anyone failing is very, very minimal considering we all went through social studies which should teach us all we need to know about American history at the very least.”

“I think somewhere along their educational experience, students do learn all of this, likely forget it, and move on. I think asking students to prepare for a test that is this topical would have the same impact,” Mrs. Quartuch said. “If we want to produce more civically engaged Americans, I think we’d need to do a lot more than make them answer basic questions on a required test.”

Senior Sarah Trebicka is a four-year staff reporter and former two-year Our World editor, now serving as editor-in-chief for the Spotlight. In addition...